Conserving Ships and Cultivating Shellfish in Connecticut

This column is brought to you by FEDS Protection, provider

of federal employee professional liability insurance.

Huey and I concluded our tour of New England in the state of Connecticut back in November. Due to a series of circumstances, including a mechanical breakdown (the RV’s), a bout of poor health (mine), and being spoiled by his grandmother for the holidays (Huey), we took a short break from The Federal Fifty. However, we are now on the road again visiting the Southeast and back to reporting on our adventures.

But first, I need to update you on my tour of Connecticut. The first federally-related location we visited in Connecticut was the Mystic Seaport Museum. Mystic Seaport is a maritime museum whose grounds hold many boats and ships as well as a replica of a 19th century village. Huey and I explored the grounds and peeked in the windows of various exhibits (as dogs were not allowed in any of the buildings). A crown jewel of the museum’s collection is the Charles W. Morgan, America’s oldest surviving wooden whaleship. She first set sail in 1841 and remained in use for over 80 years. Huey sniffed around the docks but was more interested in a pair of young children who volunteered to adopt him if he needed a new home (an offer I politely declined).

Huey poses in front of the Charles Morgan. He prefers to stay on land.

The Mystic Seaport Museum is part of the Smithsonian Affiliations program. Being a Smithsonian Affiliate, aside from providing a federal connection that draws me and Huey, allows the over 180 participating institutions to benefit from the resources of the Smithsonian to enrich their programming.

Next, we visited NOAA’s Milford Laboratory, part of the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, which was the highlight of my time in Connecticut. The Milford lab is a premier aquaculture research facility located in Milford Harbor, right off the Long Island Sound. The unique ecological factors of Milford Harbor, especially the fact that it drains and refills completely with the tides and its watershed is largely free from industrial waste, allows the lab to have a steady supply of fresh seawater. The water gets pumped to the roof of the main building and the power of gravity moves it into the facility.

Federal scientists have been studying shellfish in the area since the 1920s, when Connecticut oystermen wanted to sustain their harvests. By developing methods to replenish oyster populations at a greater rate, the scientists helped the local oyster industry expand without depleting the oyster population. This commitment to sustainable aquaculture permeates the lab to this day. Methods developed at the Milford lab are used all over the shellfish industry, not just in Connecticut.

During my visit, I sat down with three members of the lab staff: Dr. Gary Wikfors, Lab Director and Chief of the Aquaculture Sustainability Branch; Dr. Lisa Milke, Chief of the Aquaculture Systems and Ecology Branch; and Kristen Jabanoski, Science Communications Specialist. Wikfors has been at the lab since the late 1970s, when he was working on his masters’ degree. Milke has been at the lab for fifteen years. She saw a job posting for a shellfish physiologist—something that doesn’t come around every day—and has been working there ever since. Staff who have been there as long as Wikfors and Milke are not an anomaly; in fact, only two scientific staff members have been there for less time than Milke. Jabanoski, who is a contractor, came to the lab about two years ago from NOAA Headquarters. When I visited in November, there were sixteen full time scientific and technical staff. Additionally, the lab employs support staff and has visiting researchers.

Although spring is usually their busy season, the lab did have several projects going when I visited in the fall and received a grand tour of the facility. They are involved in research to cultivate offshore mussels. There are also ongoing experiments related to the effects of ocean acidification on shellfish.

An ocean acidification experiment in progress at the Milford Laboratory.

One of the remarkable products of the lab is an innovative way to raise shellfish using cultured microalgae, known as “The Milford Method.” The lab’s collection of microalgal cultures contains over 100 strains that are shared with researchers and hatcheries around the world. Before sharing the microalgae, the researchers conduct workshops to teach the recipients how to maintain their own starter cultures to foster more sustainable practices throughout the industry. Even as someone who was not previously familiar with microalgae and aquaculture, I was awestruck by the shelves of samples in a special refrigerated room.

Lab Director Gary Wikfors explains the Milford Microalgal Culture Collection.

In another room of the facility, the staff grows algae in vats, again using a unique sustainable method. Instead of draining each vat completely when the algae get used to feed various shellfish, which is the traditional method, they only drain half of the vat and refill it with fresh seawater. By replenishing the vats and allowing regrowth, the Milford lab has devised a sustainable method to maintain their stores of algae. One vat lasted for ten years, and, yes, the staff threw it a tenth birthday party.

Will these vats reach their tenth birthdays?

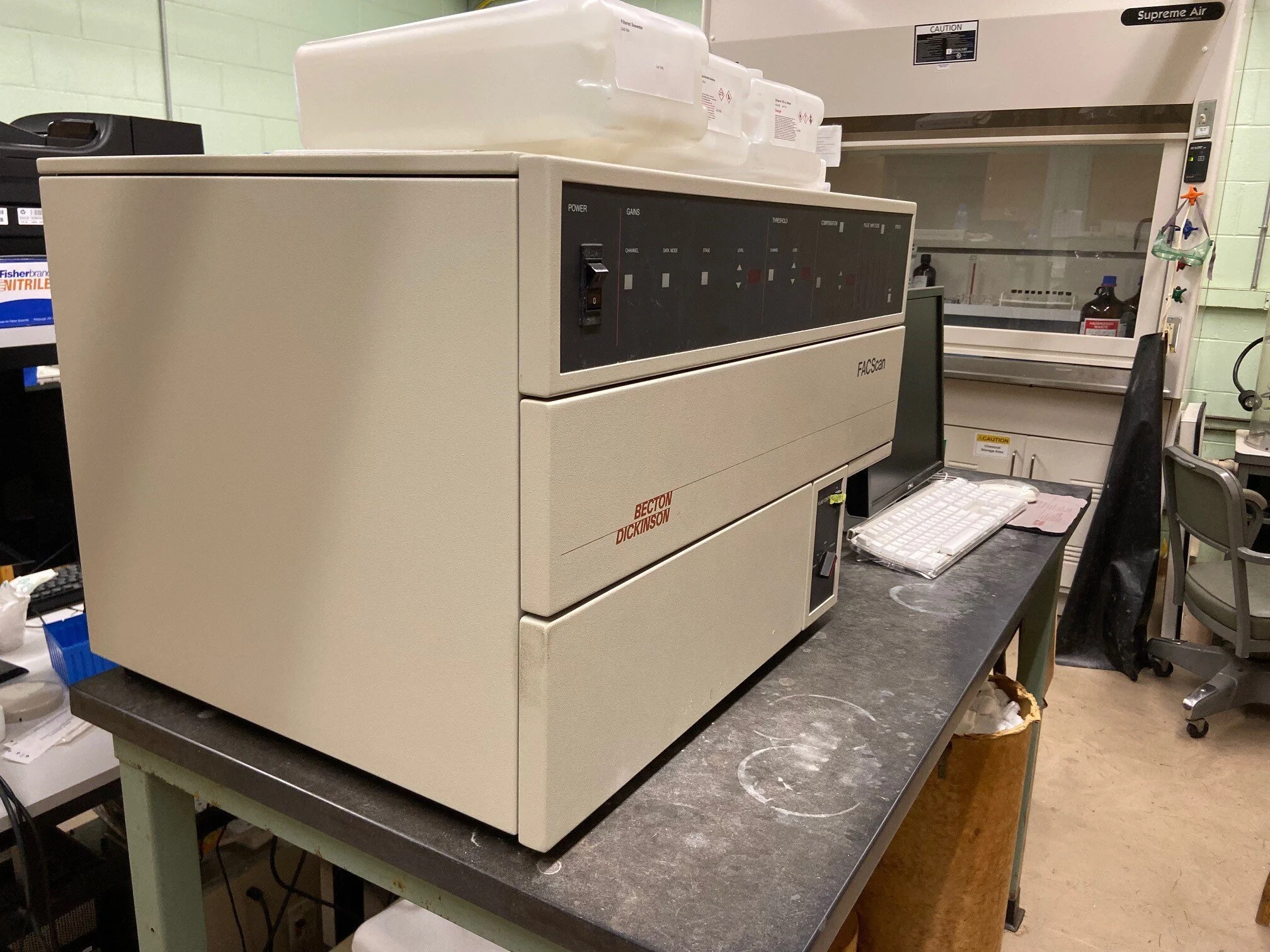

The longevity of the staff boils down to two major factors: the facility and the community. The facility—from the extensive microalgae collection to the water pumped from the harbor to the spawn room, where the staff grows their own shellfish larvae— contains multitudes of exciting resources. Their flow cytometry machines, which are usually used for biomedical blood cell analysis, draw researchers from across the globe. Because microalgal cells can be analyzed by the machines in the way that blood cells are analyzed, the lab got one of the first flow cytometers available several decades ago—so unique at the time that their machine has a two-digit serial number. The modern iteration of the machine housed at the lab is also rare—the other handful of machines in the U.S. are at major cancer research facilities.

It may not look like much, but this is one of the original flow cytometers.

The community of scientists at the lab, both currently and throughout its history, reflects the commitment to excellence that seems to flow through their seawater supply. Dr. Victor Loosanoff, the founding father of the lab (and, according to lab legend, an escapee from the losing side of the Russian Revolution who boxed lumberjacks across America before landing in New England) built the foundation of innovation and sustainability that is the bedrock of the lab’s work today. His portrait hangs in the lobby. The halls of the lab are adorned with research posters illustrating studies born in Milford that have been cited hundreds of times in the aquaculture community.

Wikfors, the Lab Director, was quick to point out that although the lab was built on the shoulders of legends such as Dr. Loosanoff, the present and future of the lab rely on collaboration. When hiring new staff, current staff look for not only the passion and commitment to excellence that they share, but also for a firm history of collaborative work.

Huey loves collaboration. Look out for his application!

I was honored to get a glimpse into such a specialized facility. In Connecticut, Huey and I saw not only the history that the government helps to preserve, but also the innovation that it facilitates and supports.

You can follow our journey in this column and by checking out our Huey-centric Instagram page @federalfifty. Please send us any comments or suggestions for future stops here.

FEDS Protection is a Proud Sponsor of The Federal Fifty Journey.

To All the Federal Employees in All Fifty States – We Thank You for Your Service.

FEDS Protection has your back so you can perform your mission with peace of mind.

Go ahead, ask around. We have a reputation for doing right by federal employees.

fedsprotection.com

You Simply Can’t Afford NOT to Have It!